Traditional Wisdom of Marine Folk

Hooking science with native

ecological knowledge and practices will help make

the proposed Tun Mustapha

Park a success writes Nadiah Rosli.

Subtle changes in the winds and currents of the

ocean have always guided Sakirun bin Abdul Rashid, a 49 year-old fisherman from

Maliangin islands of Kudat, Sabah. By observing patches on the water and

movement of the tides for instance, many seasoned fishermen like him can

intuitively expect the type of fish swimming below or when to cast their nets. When asked on how to distinguish the unpredictable

nature of the ocean, Sakirun answers, “It’s just something that us fisherfolk

know. We can tell when to haul our catch or when to return to safety.”

Pulau Maliangin © WWF-Malaysia_Nadiah Rosli

Banking on the traditional wisdom of marine

communities, a growing number of scientists are now appraising these native

knowledge and practices for its conservation value. Often times, traditional

knowledge point to when and where to fish, what fish are available, how

frequent and how many there are but it is the “why” that still remains elusive

- this is where science can anchor itself. Promisingly, it is through the

exchange and integration between scientific data and management with local and

traditional ecological knowledge that can form a powerful tool for

conservation.

BRIDGING SCIENCE AND FOLK WISDOM

Local and traditional ecological knowledge (LTK)

refers to the cumulative

knowledge, practices, experiences and beliefs of a group about their natural

environment which are transmitted in oral form. These aspects of their culture

are fluid, adjusted according to the passage of time as well as societal and local

ecosystem changes. Passed down from several generations, LTK in coastal areas

is obtained from long-term observations and experience.

Such invaluable insights have been documented in several

parts of the world. In Australia, the Aborigines have accurately observed spawning

migrations of barramundi. Fishers in Fiji recorded the local extinction of the

bumphead parrotfish through their observations and nesting site fidelity in

green turtles were first claimed by tropical sea-turtle hunters. Initially

dismissed, a research in the 1950’s by leading turtle scientist Archie Carr

confirmed the turtles’ nesting behaviour through his turtle-tagging studies.

The wealth of knowledge found in these practices has

resulted in an increasing body of literature that advocates for the bridging of

science and LTK.

The unique position of LTK are highlighted further in The Code of Conduct for

Responsible Fisheries by the Food And Agriculture Organization of the UN

formulated in 1995. Article 6.4 of the code states, “Conservation and management decisions for fisheries should

be based on the best scientific evidence available, also taking into account

traditional knowledge of the resources and their habitat, as well as relevant

environmental, economic and social factors.” Article 12.12 further

emphasized that on the matter of small-scale fishers: “States should investigate and document traditional

fisheries knowledge and technologies, in particular those applied to

small-scale fisheries, in order to assess their application to sustainable

fisheries conservation, management and development.”

According to Robecca Jumin, WWF-Malaysia Head of Marine

Programme, “Local communities act as a reservoir for LTK and their intimate

understanding of their environment is being recognised as a significant factor to the

scientific understanding of the marine ecosystem”. This extends to knowledge of

resources (e.g., types and abundance of fish species, harvesting and use of

indigenous plants), fishing restrictions (e.g., closed seasons and limits on

catch size), species behaviour and seasonal climate forecasting. She added that

in the absence of scientific data on marine ecology, the exchange of

information between locals and scientists is essential for sustainable resource

management.

COMBINED KNOWLEDGE FOR TMP SUCCESS

Traditionally, taboos and practices of locals in the

coastal communities of Sabah promote the sustainable use of their natural

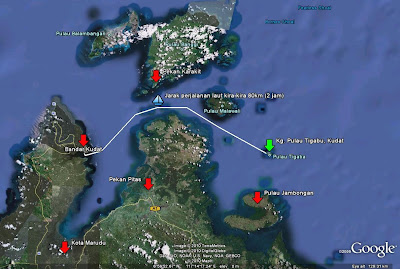

resources. This is no more evident than at the proposed Tun Mustapha Park

(TMP), an area which measures almost 1 million hectares with more than 50

islands and islets. Once fully gazetted, TMP will be the largest marine

protected area in Malaysia and the second largest in Southeast Asia. It will also be the first multiple-use park in Sabah,

based on a multiple-zoning system.

TMP boasts a rich marine biodiversity and is home to

elusive dugongs and endangered sea turtles as well as other regular visitors

such as the migratory whales. Its diverse habitats range from mangroves,

seagrass beds to coral reefs. Many components of LTK have played a role in

protecting these habitats as TMP is also characterised by a high cultural

diversity. Rife with an array of local and indigenous cultures, there are diverse ethnic groups of

seafarers and coastal communities comprised of Bajau, Ubian, Suluk, Bajau Laut,

Cagayan, Dusun Bonggi and Sungai peoples. Inland traditional farmers also make

up the unique fabric of TMP society such as the Rungus, Kimaragang, Tambanua,

Sonsogon, Murut and Kadazandusun peoples.

The success of TMP as a marine protected area will be

largely due to the combination of traditional and modern knowledge in natural

resource management. “TMP will be managed using

a multi-stakeholder collaborative management mechanism. Active participation

and involvement of stakeholders in the process of gazettement and later on in

the management of the park once legally gazetted is critical in ensuring

success and effective management. Participation of stakeholders will also

encourage compliance to plans and regulations that are being developed for the

park,” Robecca said. She added that since local communities will protect

the marine and coastal ecosystems as well as to manage the rich resources

contained within it, it is imperative that decision-making as well as

data-sharing includes these groups WWF-Malaysia has endeavoured to tap LTK

through its scientific field research with several examples validating the

experience and wisdom of the TMP community.

“For the past 6 years,

WWF-Malaysia has facilitated in the establishment of local community groups

within TMP including the Maliangin Island Community Association (MICA), Banggi

Youth Club (BYC), the Kudat Turtle Conservation Society (KTCS) and the Kudat Fishing

Boat Owner Association. These stakeholders have been involved in the designing

process of the zoning plan of the proposed park, where local knowledge was an

important base. Community members are also involved in the Interim Steering

Community as their endorsement for the process is crucial.” However, faced with

scientific scepticism, the integration and application of LTK into

formal resource management systems in the country remains a challenge. “This

process will not only acknowledge LTK as a valid qualitative knowledge-base but

also owning high conservation pedigree,” Robecca said.

REPOSITORIES OF TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE

TMP provides productive fishing grounds that support

80,000 people living in the coastal areas. Fisheries is the economic mainstay

of the area. In 2008, fisheries landing in TMP was recorded at more than 38,000

metric tonnes with a wholesale value of more than RM189 million. A valuation

study in 2011 estimated the present value of fisheries in TMP at RM561 million.

However, the proposed TMP does not escape the prevailing environmental issues

affecting other areas in the world. The advent of modernisation has also led to

superior technology which has left the area under threat from habitat

degradation and overfishing. If left unchecked, it will leave the area impoverished

in marine biodiversity and depleted of fisheries resources.

Brothers and fishermen Awang Sallehen bin Awang Harun aged

34, and Mustapah bin Awang Harun aged 42 from Kampung Taritipan, Kota Marudu

have seen the environmental degradation first-hand. They are both members of Kumpulan Belia Nelayan Taritipan (KUBENA), an organisation aimed at

improving the livelihoods of the local youth fishermen and empowering them to

become environmental custodians. With around 50 members aged 15 to 50, Mustapah

stressed on maintaining the village’s traditional ways for the fishermen’s

long-term benefits. “The villagers understand their environment more than

anyone else and we directly feel the effects when our catch are reducing or

when our rivers are polluted.” Situated along

Marudu Bay in Kota Marudu District, Kampung Taritipan has a population of

approximately 2,200 people and is surrounded by river estuaries and mangroves.

Understanding the need to conserve the beauty and natural resources of their

village, Awang Sallehen cited that community-led initiatives, such as mangrove

replanting and installation of an artificial reef, have helped rehabilitate fish

stocks. After a year, they are seeing an increase of fish in their streams.

“Under our ‘Tagal’ system where we sanction areas and times for fishing, and

conduct catch and release activities, we now have fish spawning such as

groupers, red snappers and Asian seabass. More anglers are also coming here and

we are even getting researchers from local universities who see the potential

of the mangroves in our village as a breeding ground for a variety of fish

species.”

Mustapah and Awang © WWF-Malaysia_Nadiah Rosli

However, KUBENA struggles with

individuals who are only around to make a quick buck. Mustapah lamented, “There

are some who put economic interest over conservation. These people don’t think of long-term

consequences when they do fish bombing, cyanide fishing and other destructive

fishing practices. Awareness is still a challenge and that’s why we hope KUBENA

can help increase the income of fishermen here. Gazettement of the TMP would

mean a boost in ecotourism and other prospects that will lead to further protection

of our livelihoods and environment.”

INSPIRED BY NATURAL BEAUTY

The households of Maliangin and Banggi

islands in the TMP are usually adorned with distinctive mats made from the pandanus leaves. It is no surprise then that

women on these islands have a long tradition of weaving whereby the skills to

harvest, prepare, dye and weave pandanus

leaves are now more sought after than ever.

Organised

women groups from Maliangin and Banggi produce handicrafts that are sourced and

inspired by their beautiful landscape. Sarmalin Sakirun, Secretary for the

Banggi Youth Club remarked that the project required them to canvass the skills

of older women and to rope in a younger group to learn the art of weaving. “More

villagers are beginning to realise that projects such as these can help women

earn additional income for their household needs.”

Kebun pandanus © WWF-Malaysia_Nadiah Rosli

Furthermore, the 26 year-old said that handicrafts

produced will reduce the reliance on fishing as the primary source of household

income in the area. “Most of my family members are involved in fishing. My

father is a fisherman and over the years he and my uncle have expressed their

concern over low fish stocks and destroyed corals. It’s important that skills

such as pandanus weaving which are

unique to the community here is not lost. Merging our native knowledge with new

elements such as better methods to dye the leaves and improved marketing

strategies to sell our products will take pressure of the ocean.”

Sarmalin attested to the importance of providing youth

on the island opportunities to capacity build themselves as most of them are

migrating to cities in search of better jobs. “I see potential in the

leadership of our local youth to champion for the environment. But we need them

here to lead our communities and help preserve our cultural and ecological

heritage.”

Comments

Post a Comment