STAR2: Why Destroy Sabah's Corals with Bombs?

By LEONG HON YUEN

Off the palm-fringed island of Maiga in eastern Sabah, bare-footed Ibnu Milikan is singing and fishing.

Skillfully adjusting the line’s tension, he waits patiently for the fish to bite. He admits he loves singing, which whiles away his boredom.

“There were plenty of fish 20 years ago,” he recalls. “Now there is less. Most of the corals around here are damaged. Sometimes you’re lucky, sometimes not. One, two or three fishes.”

Milikan relies on the coral reefs to feed his family of four. He learnt line and hook fishing from his father and also grows seaweed with his in-laws. “That’s the life of poor people,” he adds wistfully. “I don’t know about those who have more.”

Milikan is a first generation ethnic Bajau, a sea-faring community of subsistence fishermen living in the Tun Sakaran Marine Park (TSMP) in Semporna, Malaysia’s first community marine park. Not all fishermen have Milikan’s patience.

“During the fish season, we can get 100 kilos of fish,” recalls Anu, a former fish bomber. “We will throw explosives into the sea. One friend will look out for the marine police, the others will dive to collect the fish.”

However, fish bombing is not only illegal, it’s a highly destructive fishing method widely practiced in Sabah, and elsewhere in the Pacific and East Africa.

Coral reefs are vital for a healthy fish population.

As Marine Conservation Society UK’s Dr Elizabeth Wood puts it, “Corals only grow something like one centimetre a year, which is tiny. If the reef itself is damaged then it is less able to support life. We the consumers are in danger of not being able to get enough seafood. The price will go up because of the increasing demand.”

One study showed fish blasting in Southeast Asia costs the economy US$30mil (RM120mil) a year. It’s a prickly problem, which has been around since World War II.

For two years, my film crew and I have been filming Wood’s team and Sabah Parks as they build a unique bomb blast detection prototype codenamed Decimus.

The prototype is based on a sea mammal tracking technologyused for cetacean research. If the device can be tweaked to detect bomb blasts and alert park rangers to its exact location, it would be a world’s first attempt at an automated real-time remote system.

TSMP is about half the size of Singapore. With reduced manpower, boats and high fuel costs, knowing exactly where the crime is taking place makes enforcement much easier.

The root causes of fish bombing

Finding the root cause of the fish-bombing problem is just as important as its solution.

Why do some fishermen bomb reefs? What compels them to endanger their lives and risk capture and imprisonment?

Despite almost two decades of exposure to marine conservation as a volunteer member of a nature society, I feel I am still stepping into unchartered waters.

|

| The Royal Malaysian Marine Police accompanies the crew to the restricted island of Maiga when the need arises. |

Fish bombing is uncommon in Peninsular Malaysia. Secondly, fishing communities in Sabah are close-knit and wary of outsiders.

It takes me a year to find Anu. I enquire at agencies, non-governmental organisations and through personal contacts. Fish bombers are scared to speak to us. I receive on- and off-the-record tips that led to a particular island. A local helps set-up the meeting and we hope that Anu will agree to the interview.

For centuries, fishing has been a way of life to put food on the table; a tradition passed from father to son.

“My grandfather was a fisherman,” recalls Anu, speaking on condition of anonymity. “He fish bombed but sometimes he would do normal fishing as well. It’s the same with my father. When I was older, I followed them to fish bomb. I was 18 years old then.”

Anu’s experiences allow me a rare glimpse into his world and of the problems faced by fishermen, those with and without identity papers. Their hardship makes me more appreciative of what I have.

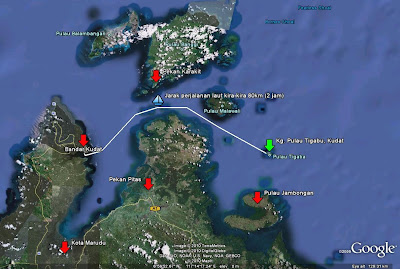

Filming in one of Sabah’s most scenic marine parks and remote reefs is a logistical challenge, more so when the deployment area of the Decimus is in the Eastern Sabah Security Zone.

A dusk to dawn curfew is enforced as part of security measures to prevent kidnapping and any form of intrusion.

Safety of the team comes first before the needs of the documentary. Our strategy is to lay low. If asked by locals, we will say we are working on a research project.

The marine park is monitored round the clock by security forces. As a precautionary measure, we keep only essential people in the loop of our daily whereabouts.

And when the need arises, for example travel by boat to a restricted island or a remote reef, we request a Royal Malaysian Marine Police (RMMP) boat to accompany us.

From producing and directing, this film has been the most challenging documentary we’ve done to date. There are teething problems with Decimus and we have to be always mindful of the tides if we want to access coastal villages.

We also learn very quickly that shoot schedules made in advance often have to be quickly abandoned sometimes.

Sabah Parks enforcement ranger Abdul Hafiz Matlah is one of our key characters and also the investigating case officer. His interview has to be momentarily put on hold. Wood and her colleague Jamie Valiant Ng are busy checking reefs so we have no access to them. The imposing volcanic islands are also veiled in thick smoky haze.

What can we do? We disappear underwater to film the wonders of the marine park’s living creatures!

Finding funds to make documentaries is always a challenge. The documentary is a result of a pitching opportunity to a development fund competition organised by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC).

It took us a year to win one of the grants, but at the 11th hour, rules changed and instead of three films, five films came out of the competition as winners which had to share the money.

Despite the shortfall, we completed the film because we thought it was a story worth telling with an important environmental and social message. The film was finished with money raised from crowdfunding and from my own company Factual TV. The production crew worked without pay for one third of the filming days.

Essentially we are a small team. Everyone multi-tasked. Cinematographer-cum-editor Chi Too and location sound recorder-engineer Syahreez Redza joined the competition from the start.

We finished the shoot with Sabahan camera-sound assistant Syaiful Adzwan Hashim and a filming unit in Scotland. Our key post-production team comprised two Malaysians and a writer from New Zealand.

In Asia, the film featured on the History Channel earlier this year under the title Tracking Asia’s Fish Bombers. Internationally, the film is being distributed as The Bomb Listener.

When you work on a film as long as two years, with people at the frontlines of marine conservation and the nation’s security, you are privy to the work they often do with little recognition. I’m honoured to meet them as well as Milikan and Anu. I wish them all well.

Tracking Asia’s Fish Bombers will be shown Nov 1 at 11pm on the History Channel (Astro Ch 555/HD 575).

Source: http://www.star2.com/living/living-environment/2016/11/02/why-destroy-sabah-corals-with-bombs/#b9ac86WLUbsCLhyG.99

Comments

Post a Comment